Thanks for funding: Finnish Cultural Foundation and TAIKE Finland

The Papercraft publication is a description of the use of paper as a tool for art, written by an arts worker and design amateur for people like him. It is a document about works of art and the thoughts they produce. The text is based on direct experiences of work processes and insights gained from them. These insights have invigorated and changed my work habits.

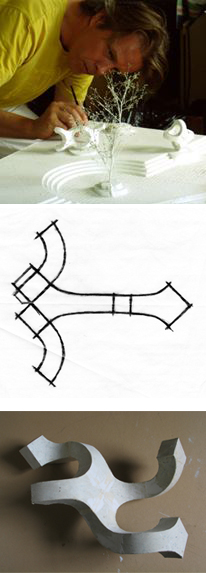

I do not represent the viewpoint or theory of a professional in any scientific, design or art field. I am presenting the use of paper as a flexible material for examining an experimental structure and shape. Paper is a tool for the person, who wants to create for himself or herself an experiential perception of the dimensional basic structures of shapes. This means a 3D programme, which develops in the creator’s own mind and is based on a physical event and world. The idea of experiential learning and methods was developed in the basic instruction of Bauhaus design, for example, by using recyclable light materials, such as paper and cardboard as a research tool.

Josef Albers paper class 1927-1929, in Bauhaus school, Germany

In the words of one coach, “Experience is not what happens to us, but what we learn from it.”

On the understanding of shape

I will tell about my own way of perceiving structures and shapes. How I see them as. In my work, I am trying to understand the ways different shapes are constructed figuratively and through experimentation. My working order has been created by experimentally moving from a simple shape to a more complex one and back again. Paper for me is a tool for physical self-learning born from curiosity and an obsession led by imagination.

A good understanding of shape usually refers to an ability to perceive tridimensionality and the skill resulting from it to reduce that “eye’s know-how”. Even a vague general view of the basics of paper design is necessary if the creator wants to learn to use them as his or her premises for reaching his or her own recognisable style, or then one can “go directly to where no one has ever gone before, without guidebooks and not caring about styles.” As if one really needs to, style is its creator’s personal quality characteristic, which becomes visible by itself through know-how and the manner of processing that which is seen. Repeated basic structures and shapes could be imagined as recognisable landmarks, planets when moving in a hyperbolic space.

Furthermore, one can enjoy a good understanding of shape when one is already able to build and use various shapes and surface materials fairly effortlessly, as if knowing on the basis of one’s experience what and how one could and should make from them, how they work or what they endure, how to use tools etc. This kind of experience base and thoughts rising from it cannot be obtained only through reading.

In art and design, the road from an idea to a clear work plan is always long. Sometimes an idea that feels ready is a hindrance, and the plan is not realised as such in the artefact or presented final product. Ideas would be boring if they would not develop into something else as well during work and its doing. As a matter of fact, concrete work, modelling and time-consuming drafting test the importance of the idea and considered work. They are examples of practical brainstorming, in which the creator wanders in order to map out alternatives and test his or her thoughts.*

Through paper design, I am able to view blocks or design products by people more clearly and deduce how they are done based on my learning/experience. I have the ability to enjoy their functional structure and the beauty resulting from it. I can also see what is missing from the objects, how they are lacking in their usability or where they have picked their likenesses and ideas from. This kind of viewing and valuation method could be called recognising quality. In the best case, we can also learn a little about how the physical world and natural shapes grow and are built.

Thoughts on the relationship between structure and shape

Structure in this publication refers to the method of doing or order with which the parts of the shape are attached/or attach to each other at each time.

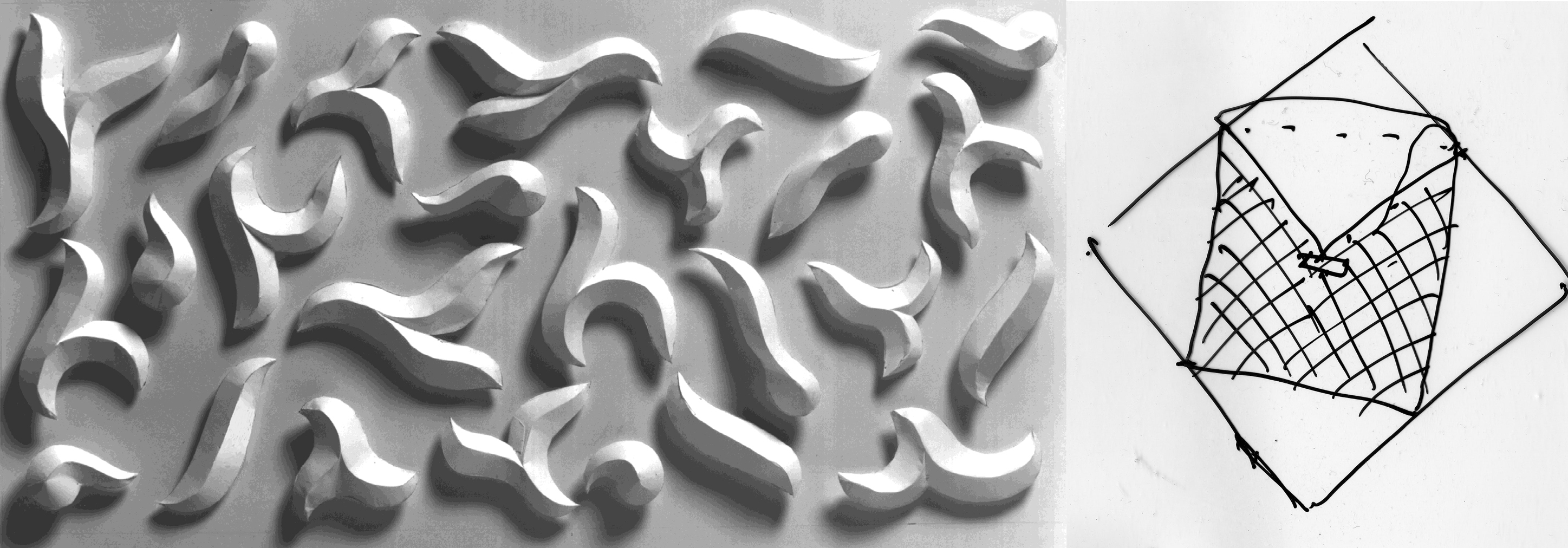

The basic method to work the paper and other surface materials could be considered to be folding or bending, cutting a spread slab or diagram, forcing it into its shape, attaching and compiling from spokes and parts or weaving the shape from separate strips. A sheet of paper is so light and flexible that the weaknesses of the used structure are easily exposed in the shapes made from it. Therefore, I will not write much about the shaping of a paper mass with a mould or net, but instead the cutting or bending of a sheet of paper, as is done in origami or packaging design. Paper can also be used as a key to other materials, planning, for scale models etc. It gives tips on what and how one can build sustainably.

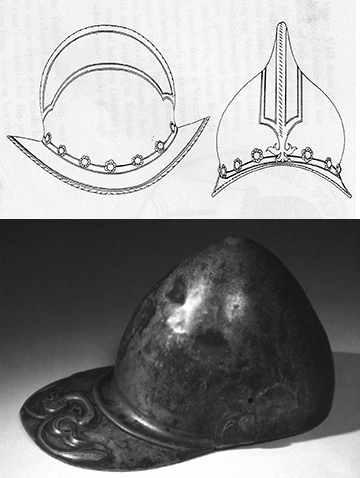

Many handicraft methods and skills, a metalsmith’s processing of a plate, a shoemaker’s leather work and a tailor’s work with fabrics are related to paper design. Work on metal has largely been the processing of rolled sheet metals by bending and forcing. In them, the smith has known the principles of curved bending, which is shown, for example, in various tin roof structures or details of armour. Indeed, the impact of structure on the shape, materials and methods of doing are matters that should be emphasised and observed separately, before considering the final shape of one’s work at all.

In old handicraft methods, the object’s function and what was available determined the material, a certain method of doing suited the material and the used structure determined the kinds of shapes created. The weaving of the Finnish traditional shoe, i.e. birch bark shoe, was usually started at the bottom underneath the foot as a flat lattice, bent up from the edges on top of the foot and the woven strips were turned into an opening through which the foot pushed into the birch bark shoe. Then another layer was woven on top as the exterior. The shape and method of doing varied according to the weaver and cultural region, but the foot always had to fit in it. Furthermore, the wrapping of the foot in paper, leather or fabric provides a mental image of what kind of an organic structure and shape is suitable for a good shoe, where to put the seams and where are the fastenings?

Indeed, weaving, the weaving of nets or interlacing of surfaces has been done from natural fibres, as from shingles or birch bark in Finland already from early times. (Ylimuistoinen tuohi – Immemorial Birch Bark, Sirkka-Liisa Ranta, 2016) Weaving deals with how the surface can be widened by increasing and reduced by pleating. The creator can, if desired, continue working all the time in as many directions as she or he has the strip ends in his or her hands. The surface has not been readily cut or the size specified as in plate work.

By experimenting, a cube can further be made from paper strips at right angles in the direction of the sides or then with a slanted transverse structure, whereupon the structure and shape are stronger and the strips circle the shape’s extremities in a slanted direction. Indeed, folding and weaving in a slanted or direct direction are two basic ways to perceive an object’s shaping possibilities, and they have been used side by side always according to the use and the creator’s skills.

A birch bark container is in itself a rectangular twine woven into a diagonal, whose edges are folded up and tied off in the middle and of which one remains the flap lid of the container’s mouth.

The basic structures come out in the basic shapes

An understanding of the structure brings out the idea that an individual basic shape is not important at all, because the basic significance is in the way of combining and presenting different structures and in this way apply curved, round, helical or angular shapes for different uses. The essential thing is how we build, thereby the order creating a ready shape and the dimensions of natural growth validated and used by man of his environment.

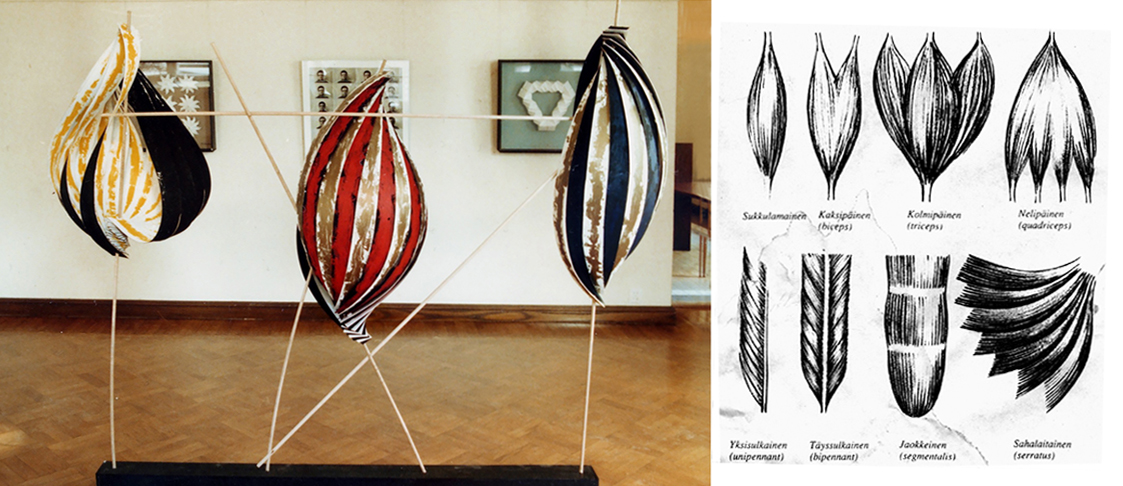

Shape is created as the end result of the used functional structure and growth, sometimes without design forced by the structure. Much helicity occurs in nature, due to which the structure of the shape is stiffer and stronger, like a direct construction. Helicity can also be called a voltage, a power that in some shapes is directed outwards as in football and in other shapes is squeezed completely inwards. In addition to rhythm, dance consists of a very expressive spinning motion. Muscle types in human anatomy are, for example, kinds of reversible springs, whose number of fastening points varies.

Wild plants grow into spirals due to the effect of the sun’s rotation and with their structure reach an adequate strength for bearing the weight of their fruit. When a shape grows, it spirals open, like buds. Many round helical structures appear in nature, such as snails, clams etc. organic shapes growing in a spiral manner.

One can experiment with and build helical shapes from paper strips in different ways. What the strips have in common is that they only utilise a few basic structures while trying to form a tridimensionality as strong as possible.

Indeed, we should have a more experiential perception of the behaviour of matter and geometry in reality, so we could perhaps know to wish for significantly better 3D programmes, which would not repeat geometrical basic shapes, but instead would be based more on the ability of structures to manage shape. This, of course, requires materiality from the programme, in other words, the ability to recognise and simulate the behaviour of each material. Growing in nature requires the ability to change and become more complex from a living shape that has been born – for this reason, the structure must have the ability to be flexible and recover. This characteristic is visible also in paper precisely due to the tension in the structure of the paper’s shape.

Diagram knowledge has an important role in clothes design. It uses and repeats many curves of different degrees and the setting of different cylinders into each other to dress the anatomical details of man in its clothes. Creativity is used by considering, for example, what kinds of flat parts the piece of clothing consists of, in other words, where the seams are located at each time. It radically impacts the shape of the piece of clothing. Good bakers or pastry makers have also always known how to make scrolls, cylinders and crusts of their disc of dough for their delicious fillings. These shapes are simpler than a tetra or a dodecahedron and sometimes resemble snails or helical clams. They, too, are located somewhere in our shared memory. The lofty purpose of the basic shapes of Plato and Euclid’s geometry may have been to make visible and preserve something that exists irrespective of us, but that everyone can find.

Finding basic shapes in paper through practical exercises does not require a deep familiarisation with theoretical geometry etc. Experiential learning, dimensional accuracy and making observations does not always enable verbalisation. When a man from an early hunting culture has at some point learned to make a small drinking bottle in the shape of a regular polyhedron from doubly woven birch bark as a side product of basket weaving, that skill is also within our reach, without any kind of a model. The bottom of a birch bark bottle is the shape of a square and the sides are formed of eight triangles, whereupon the shoulders of the bottle are settled in the middle part of the bottom’s sides. Then the neck of the bottle narrows and the sides coil beautifully into a durable cylinder to end up in the finalised open mouth of the bottle.

Kai Rentola